7,906 views ·

11 replies

8k views

11 replies

Moist additional insulation of brick wall

Hello,

to make a long story short; I bought a 1920s house that I am completely renovating! The kitchen wall you see in the picture is constructed as follows: Brick > plaster > wind barrier > studs > insulation > chipboard > drywall.

Stupid as I was when I did the kitchen some months ago, I decided to draw the line somewhere and just slapped drywall on the wall! Now a couple of months later, there is a faint musty smell that tends to cling to plastic bags and fabrics that are placed next to the wall!

I made a hole in the wall and could confirm that the chipboard that the wall stands on had a moisture content of 30% yesterday, and now when I took the picture it had dried out a bit!

The floor is cast with 100mm of cellular plastic on top of the concrete and floating chipboard on top! Whether there are capillary-breaking masses underneath, I do not know!

The floor chipboard also seems to have no direct contact with the brick wall, so I was surprised that it had 30-35% moisture yesterday when I opened up the hole!

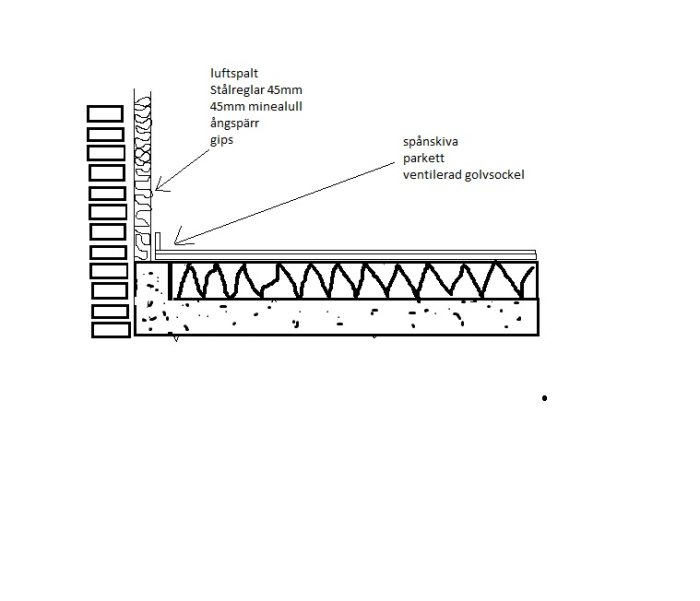

My first thought was to build a new wall with steel studs, 45mm insulation, vapor barrier, and drywall, but now I'm afraid that if I replace the bad floor chipboard and build up a new wall, the floors will probably become moist again!

Does anyone have any thoughts or ideas?

to make a long story short; I bought a 1920s house that I am completely renovating! The kitchen wall you see in the picture is constructed as follows: Brick > plaster > wind barrier > studs > insulation > chipboard > drywall.

Stupid as I was when I did the kitchen some months ago, I decided to draw the line somewhere and just slapped drywall on the wall! Now a couple of months later, there is a faint musty smell that tends to cling to plastic bags and fabrics that are placed next to the wall!

I made a hole in the wall and could confirm that the chipboard that the wall stands on had a moisture content of 30% yesterday, and now when I took the picture it had dried out a bit!

The floor is cast with 100mm of cellular plastic on top of the concrete and floating chipboard on top! Whether there are capillary-breaking masses underneath, I do not know!

The floor chipboard also seems to have no direct contact with the brick wall, so I was surprised that it had 30-35% moisture yesterday when I opened up the hole!

My first thought was to build a new wall with steel studs, 45mm insulation, vapor barrier, and drywall, but now I'm afraid that if I replace the bad floor chipboard and build up a new wall, the floors will probably become moist again!

Does anyone have any thoughts or ideas?

So there is no moisture barrier (plastic) in the insulation/wall?

In that case, it's not good to have wood there at all!

The moisture can also come from the slab, and it's an uninsulated slab on the ground.

I have a similar wall in my split-level house but in lightweight concrete that drew in moisture so the plaster and paint flaked off. I installed steel studs against rubber (to avoid possible corrosion) and then plywood and drywall. I placed an Östberg facade fan on the outside in the middle of the wall and have two air intakes with regular vacuum cleaner filters down in each corner...

Guaranteed moisture-proof!

In that case, it's not good to have wood there at all!

The moisture can also come from the slab, and it's an uninsulated slab on the ground.

I have a similar wall in my split-level house but in lightweight concrete that drew in moisture so the plaster and paint flaked off. I installed steel studs against rubber (to avoid possible corrosion) and then plywood and drywall. I placed an Östberg facade fan on the outside in the middle of the wall and have two air intakes with regular vacuum cleaner filters down in each corner...

Guaranteed moisture-proof!

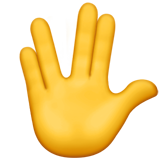

I don't think this is a correct description of an exterior wall in a 1920s house. Firstly, there must be a solid plank frame (2-3 inches thick) to which the wind barrier is attached, and which provides the structural support in the wall. Secondly, the brick must have been applied afterward, as there is a plaster layer behind it. I don't think facade bricks were used in the 1920s; only full-layered brick exterior walls existed. Facade bricks must always be built with a ventilated airspace behind them. As a result of the brick being directly against the plaster, the brick's moisture is transferred to the plaster layer, which cannot dry out. The paper behind the plaster should have been an asphalt paper, but it has probably lost most of its moisture-insulating ability.O otto123 said:

Before I extend my theory further, I would like to know the actual construction of the wall. If you can provide some depth measurements, it will make understanding easier.

Sorry, my description was a bit unclear! The existing additional insulation was added in 1991 when the kitchen was renovated! The frame of the house is brick, kanaltegel, there is no plank wall, it's solid walls!

To specify the whole wall from outside to inside, it looks like this: Plaster->Brick->Air gap->Brick->Inside plaster->Air gap->Vindpapp->Wooden studs & insulation->Chipboard->Gypsum

No, it's ordinary forhydringspapp (vindpapp) that was directly against the inside plaster! Probably because they thought the wind was coming through the brick frame!

To specify the whole wall from outside to inside, it looks like this: Plaster->Brick->Air gap->Brick->Inside plaster->Air gap->Vindpapp->Wooden studs & insulation->Chipboard->Gypsum

No, it's ordinary forhydringspapp (vindpapp) that was directly against the inside plaster! Probably because they thought the wind was coming through the brick frame!

Then it looks much more normal! Is it the plaster one sees in the photo where you've removed the particle board? Bricks plastered on both the outside and inside usually don't need additional wind proofing. Was plastic sheeting used when the kitchen was additionally insulated? When additionally insulating such a wall construction, plastic sheeting should not be used for two reasons. Firstly, it is not needed as any condensation of indoor air's water vapor occurs in the brick wall, which tolerates moisture. Secondly, it contributes to creating an elevated moisture environment in the additional insulation layer. One should also not have a vapor barrier paper on the inside of the wall as it hinders the passage of water vapor. I believe in an air gap between the wall and the metal studs.

It is likely that at least part of the problems are related to the floor construction, but I need to understand a bit more about how it looks. Does the concrete slab lie directly on the ground? If so, it is very unusual for a house from the 1920s.

A bit unstructured, but the problem seems complex.

It is likely that at least part of the problems are related to the floor construction, but I need to understand a bit more about how it looks. Does the concrete slab lie directly on the ground? If so, it is very unusual for a house from the 1920s.

A bit unstructured, but the problem seems complex.

Yes exactly, it's the render you see! No, there was no plastic wrap in the wall!

I was a bit unclear again! I THINK that the concrete slab in the kitchen was cast when the kitchen was renovated in 1991! But whether it lies directly on the ground or on capillary-breaking materials, I don't know! I'd have to chip away a bit to see, and that feels a bit drastic!

I was a bit unclear again! I THINK that the concrete slab in the kitchen was cast when the kitchen was renovated in 1991! But whether it lies directly on the ground or on capillary-breaking materials, I don't know! I'd have to chip away a bit to see, and that feels a bit drastic!

No, don't dig up anything. What does the foundation look like from the outside? There isn't a basement, right?

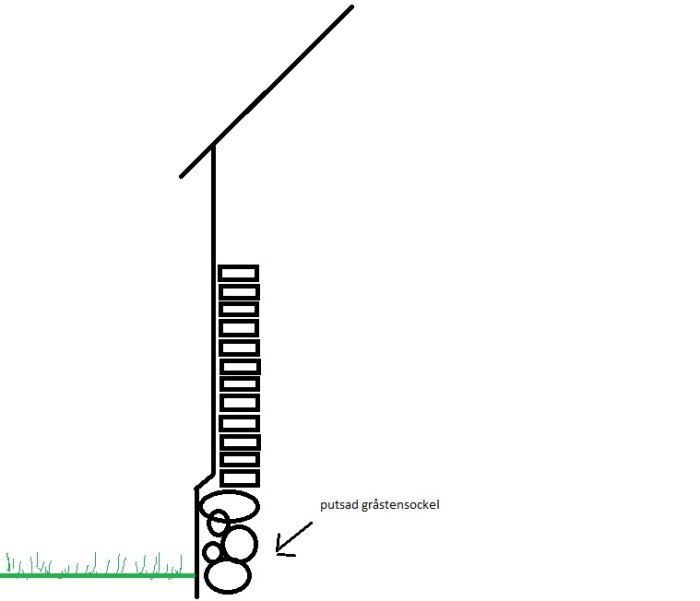

Yes, that's what I suspected. The concrete is likely cast on top of a layer of compacted macadam. There may be lecakulor or styrofoam under the concrete. It should be if it was done in 1991, but that contradicts the styrofoam on top of the concrete. The concrete is probably up to 10 cm. Capillary action of moisture from the ground I think we can rule out. If your first section is correct, i.e., there is a concrete ledge on the outer edge against the exterior wall, then I think the main cause is there. That part of the concrete will always be moist. Is the chipboard directly on the concrete?

Good question, I'll probably need to look it up and get back to you with an answer tomorrow! In the other rooms, there has been a soleplate cast, probably since the house was built, on which the brick has been laid, and it goes 20 cm inside the brick! So most likely it's the same in the kitchen!

But if we entertain the thought that the chipboard is close to or in direct contact with the concrete there, how should one proceed then?

I find it hard to explain, so I'm attaching a picture of how it looks:

But if we entertain the thought that the chipboard is close to or in direct contact with the concrete there, how should one proceed then?

I find it hard to explain, so I'm attaching a picture of how it looks:

Last edited:

Sill paper is commonly used to isolate wood products from concrete that can be damp.

Click here to reply